“What the Hell is that Supposed to mean, HAL?”

Introductory remarks on the screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey; or, Communique #7 from the Institute of the Mechanical Surround (11.13.24) <<<<>>>>

As co-director of the Institute of the Mechanical Surround, I am excited to be here with you tonight and to introduce Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey. And I am grateful to Jeremy Moss for inviting me to say a few words before we press play.

I have much to say, too much, really. I will start by stating the obvious: We are living through a long season of algorithmic enthusiasm. And although our excitement may tend toward the solitary pleasures of the screen, we are infused with the spirit of revival. We effervesce and we orient ourselves not to each other but through a collective capitulation to our devices. We are willing subjects, performing and playing out the roles that we have assigned ourselves in this drama that is both sacred and secular.

This is an observation I learned to make some 30 years ago when I first saw 2001. Stunning at the level of form and content, 2001 tells the story of a species living through what amounts to the early stages of some new and unapproachable state of affairs. Some might call it a rapture and others a rupture in evolution. Either way, it is generated by the capacity for machines to recognize patterns of human being and to imitate, beyond a shadow of a doubt, intelligence and much else besides.

As a young graduate student in the study of religion I can still recall Kubrick’s highly stylized and operatic sequences conjuring something that was not simply transcendent or extra-terrestrial but a beckoning force reserved for the Gods of the missionaries that I was studying.

Kubrick himself came of age of in the cybernetic frenzy of the post-war years and observed, first-hand, the zeal of techno-militarists and those who peddled, in the laboratory and in the newsroom, the good news of artificial intelligence.

JCR Licklider, for example, director at the U.S. Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the central go between the American military, business, and the academy in the 1960s was one of many who worked diligently toward the goal of what he called “man-computer symbiosis.” In 1968, the same year that 2001 premiered, Licklider predicted that “In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face to face.” Having “confessed quite personal relationships with his machines,” human intimacy for Licklider did not depend upon “seeing the expression in the other’s eye.”

The siren call of the computer has not abated since 2001. And the fruits of its success are now everywhere about us, marked by a gleeful submission to surveillance, an enthusiastic embrace of machine learning, and a widespread longing for correspondence with a macrocosm that is dynamic, multi-dimensional, self-organizing, automatic, and therefore considered universal.

Which is to say, the prospect of automating our material, biological, and emotional worlds involves a commitment, a metaphysical one at that, to a particular kind of human being, or at the very least, particular type of human drama.

This drama, then, this movie of our own making, has all the markings of a snuff film. We are actively, aggressively, even gleefully staging a production in which the central drama revolves around our own annihilation and the pleasure that it entails. The machines, in other words, are not entirely to blame.

2001 is a movie about this snuff film that humans have been producing, perhaps from the dawn of time.

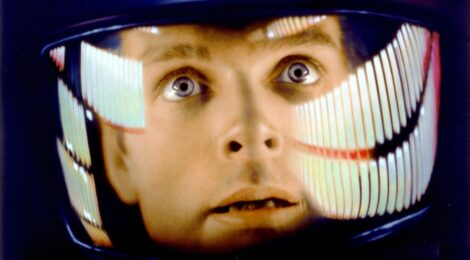

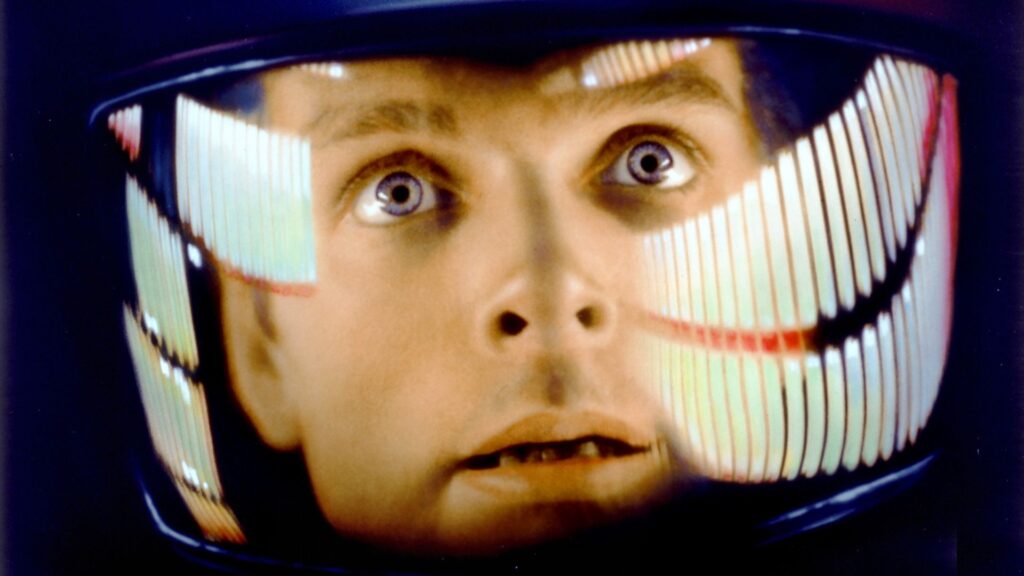

2001 is perhaps most iconic for its portrayal of HAL 9000, an artificial intelligence whose human-like characteristics distilled decades of cybernetic anxiety over the prospects of building “giant brains.” HAL is certainly ominous but HAL is also cartoonish, a projection, a false positive, a would-be god whose will to control can and will be thwarted, a tragic figure who ends up limited by his all-too-human programming.

Kubrick’s cartoonish scenario of machine mischief remains a plotline of contemporary AI boosters and critics alike—robots helping us over the finish line of human destiny OR robots squashing us with their superiority.

But as Kubrick’s film suggests, this is a rather cartoonish and juvenile understanding of what is happening, as if humans are or will soon be removed from the process of constructing our reality. This cartoon also perfectly distracts from the even more disturbing fact that the humans in 2001are already on the very cusp of being fully incorporated/incorporating themselves into the machine.

As a writer, my concern is not so about HAL-like robots convincing us through computational charm and mathematical guile but rather, I am utterly terrified by the prospect of humans convincing themselves, one doomscroll at a time, to lean into the automation of their own cognitive and imaginative skills. This is a seemingly an undramatic process. At first we jettisoned the typewriters and pens. Then we jettisoned the spelling, the space between letters. And then we forgot the rules of grammar, the space between words. And then we outsourced the sentences and the space between sentences and, eventually, the space between individuals and, then, whatever differences or peculiarities lie within each of those individuals.

But 2001 begs an important question for me: what, exactly, is animating these decisions and habits, these lapses, apathy, and addictions? What kind of God or near-human power have we humans dreamed into being?

The material and abstract power of technology courses throughout the sets and scenes of 2001 but congeals most dramatically in the totem that is the black monolith, a deadening and deafening presence that appears here and there and drives the plot along.

The black monolith is mind-boggling in its power to redefine social relations on a dime, to effect evolutionary advance, to lie beyond space and time, The monolith channels the power of some kind of God. It signifies and signifies without, itself, being subject to signification.

This is the power emanating from and fueling our technological moment. But might I also suggest that the monolith is the power of dreams, the power of the artist, the terrifying power of what lies outside the algorithm.

Ambiguities, all the way down.

I would like to think Kubrick would agree. But, then again Kubrick was also not a writer. “2001 is a nonverbal experience” quipped Kubrick a few years after its premier in 1968, “one that bypasses verbalized pigeonholing”

So with that said, I invite you to open yourself up to an encounter with a movie that is out of joint with the current moment. If you have not experienced 2001, I am so jealous because it’s a movie that torques hard against the contemporary sensorium. It’s rhythm is not 24/7. It’s rhythm is what earlier generations may have called cosmic.